Friday, February 25, 2011

A Fight over the "Hidden Los Angeles"

For those who have not seen or heard of this, the site's mission is to give "locals a reminder to leave the house and get inspired" about things in their city that they have either forgotten about or simply have never discovered. Lynn, the site's creator, compares the city of L.A. to one big TJ Maxx. For the girls in the class, the metaphor absolutely stands true. Los Angeles might seem like one big grey city that is scary to some and uninteresting to others but once inside there are amazing treasures to be found. The site hosts contests for people to write in about their favorite Los Angeles spots hoping to win prizes like tickets to the Opera House. The freebies off the site are refreshing to see. Lynn obviously has so much passion and belief in Los Angeles that she is willing to spend her time creating and brainstorming new ways for people to get out and actually DO things, things that aren't the norm.

The site, in my opinion, has every right to stand up for their ideas and ingenuity. I urge you all to check it out and also take a look at the site's "Story and Mission" tab. Reading it, it sounded like Professor George talking on our first day of class. Lynn simply loves the city and though she admits it has its flaws, she knows that there is more to the city than what is expected of it. She challenges the site's visitors to go find these places similar to our challenges as a class. Check it out!

http://hiddenlosangeles.com/

--Katie Mollica

Photo: hiddenlosangeles.com

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

Monday, February 21, 2011

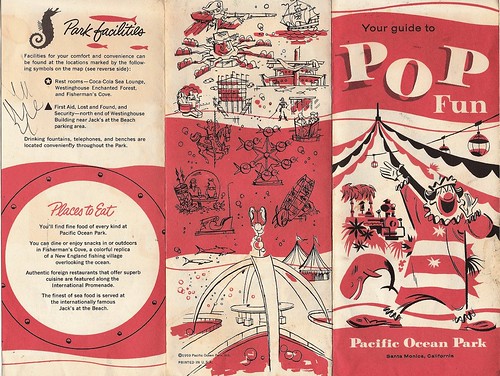

Pacific Ocean Park

AS a “theme park enthusiast” of sorts, the video of Pacific Ocean Park from class immediately caught my attention. I had never heard of the POP on the Pier, seeing as it was only around for roughly ten years. With the opening and overwhelming success of Disneyland in 1955, it seems only logical that Los Angeles would want to jump on the theme park bandwagon as well. From what we viewed in the clip, it was clear to see that they were trying to appeal to the idea of modernity that was prevalent during the 50s. But what I found interesting was the location chosen for this nautical yet futuristic park. The fact that it was placed on a pier made it reflect back on the pier theme parks and attractions of the East Coast, rather than creating its own Los Angeles identity. Was this intentional? Perhaps Los Angeles was trying to attract tourist crowds but also mirror the culture of the East Coast attractions as well. POP was initially met with high crowds and success but when Santa Monica began an urban renewal project of Ocean Park in 1965 it made it difficult for tourists to reach POP. This resulted in a drastic loss of attendance and the ultimate destruction of the park. Personally, I feel like the role of an amusement park in Los Angeles is unnecessary. LA is already an immensely popular tourist destination in itself, the addition of any major theme park, then or now, could seem superfluous.

--Reilly Wilson

image: pacific ocean park brochure

courtesy, robert huffstutter via flickr creative commons

The Profile: Roger Ebert

THIS, of course, is not quite about L.A. but it is about the "factory" that makes its home here: Hollywood and movies. Last week, we talked a bit about the arc of the profile and I shared some samples of stories with the class. Below, you'll see another link as well -- "ways in" to a story, but I wanted to post Chris Jones' Esquire profile about film critic Roger Ebert's battle with cancer here and, today, Ebert's own response in the Chicago Sun-Times, his hometown paper. Below, a sample that speaks to what we discussed about observation and a writer's choices (note the comment about the "commissioned portrait"):

THIS, of course, is not quite about L.A. but it is about the "factory" that makes its home here: Hollywood and movies. Last week, we talked a bit about the arc of the profile and I shared some samples of stories with the class. Below, you'll see another link as well -- "ways in" to a story, but I wanted to post Chris Jones' Esquire profile about film critic Roger Ebert's battle with cancer here and, today, Ebert's own response in the Chicago Sun-Times, his hometown paper. Below, a sample that speaks to what we discussed about observation and a writer's choices (note the comment about the "commissioned portrait"):It was also well written, I thought. "When I turned to it in the magazine, I got a jolt from the full-page photograph of my jaw drooping. Not a lovely sight. But then I am not a lovely sight, and in a moment I thought, well, what the hell. It's just as well it's out there. That's how I look, after all. . . . . My theory was that if Chris had an article to write it was not my place to write it for him as a favorable press release about myself. Let him write what he observed. Oliver Cromwell is said to have commissioned an official painting of himself, "warts and all." He apparently never said any such thing, was misquoted a century after his death, and his official portrait showed no warts, but never mind: He should have said it."

-- L.G.

photo caption: Film crtic, Roger Ebert

photo credit: Esquire magazine

Sunday, February 20, 2011

The Profile: Norman Klein

AS DISCUSSED, in class, I wanted to post some examples of the profile at work. Here is an example of a profile written by David L. Ulin about social critic Norman Klein. Play close attention to the structure of the piece. How the lead/opening works, how Ulin handles quotes, the scene setting and how the city emerges in the piece . . .

City of Ruins: By Excavating the Hidden Past, Norman Klein has Emerged as L.A.'s Most Innovative Social Critic

By David L. Ulin

One evening early this fall, Norman Klein sat behind a formica table, speaking softly but insistently to a small audience at REDCAT, CalArts’ performance space that occupies the rear end of Disney Hall. Beneath the table, his right leg tapped a mile a minute, like a metronome. Wearing unpressed khakis and a white button-down shirt, hair exploding in a wiry gray corona, he had the slightly disheveled look of an absent-minded professor, which, in some sense, is what he is. For 30 years Klein has been on the faculty of the School of Critical Studies at CalArts; in addition, he teaches in the graduate program for media design at Art Center. But recently he has emerged as the most innovative Los Angeles social critic since Mike Davis—fast-talking, omnivorous, a bantam-like urban theorist with heavyweight ideas. His 1997 book The History of Forgetting: Los Angeles and the Erasure of Memory put into language what many residents have long thought about L.A. — that this is a city where meaning has as much to do with what we don’t see as what we do. The notion also motivates his 2003 novella-cum-DVD-ROM Bleeding Through: Layers of Los Angeles 1920-1986, which he had come to REDCAT to discuss.

Bleeding Through is one of those transformative works—Klein has described it as a “data/cinematic novel”—in which the form is as innovative as the content. Framed as the story of an old woman named Molly, it blends fiction, social commentary, and historical analysis in a multimedia pastiche of 20th-century L.A., constructed around a vast electronic archive of what Klein calls “traces”: photos, news clippings, interview footage, snippets of documentary and dramatic films. If this sounds compulsive, that’s the point precisely; “I’m obsessed,” Klein enthused at REDCAT, “with the idea that the evidence is almost as exciting as the story. I find it so interesting to locate bits and pieces, scars of how memory works.” For him, such a process seems particularly suited to Los Angeles, “a city,” he writes in The History of Forgetting, “that was imagined long before it was built.” Bleeding Through, then, reflects L.A.’s own unreliable memory, a notion Klein (and his electronic collaborators) highlights by weaving “forgetfulness” directly into the project’s software, which brings up different material from the database each time you load it, so the story never unfolds the same way twice.

The idea that L.A. is inherently elusive — a fragmentary landscape of glimmers and glimpses — can get a little abstract, which may explain why Klein has taken so long to catch on. With the exception of the Los Angeles Times, his books have been largely ignored by the media. Partly, this has to do with how Los Angeles intellectuals are treated. “For some reason,” says Peter Lunenfeld, who teaches with Klein at Art Center, “L.A. only has room for one public intellectual at a time, and now it’s Norman. It’s like we can’t handle more than one conversation at once.” Partly, it is Klein’s professional status, the way he straddles several disciplines at once. If you ask, he’ll tell you he’s a writer, as opposed to a theorist or professor, then cite influences as diverse as Baudelaire and Balzac, Faulkner and Joyce. Certainly, his career can be hard to classify; untenured, he has been an adjunct at UCLA, Otis, Sci-Arc, and USC, moving from campus to campus like an itinerant, leading a patchwork academic life. His course descriptions read like outlines of his obsessions, with classes on the history of simulation, or the buying and selling of L.A. as fantasy. “You set up a problem you want to solve,” he says, his Brooklyn accent muted with resignation, “and it forces you to do research. Teaching at art schools, I don’t have the degree of support I’d get from a research institution, so I have to build it in.”

If Klein is difficult to pin down, the same could be said about Los Angeles, which reveals itself in the most unlikely spaces, spaces we might never think to look. “Did I ever tell you about the ugliest place in Los Angeles?” Klein asked me one afternoon in his office, a converted garage behind his house in Highland Park. Although we were sitting together, he peered into the middle distance, face growing animated and his voice rising slightly, as if he were a kid with a secret to impart. “I decided it was in Van Nuys, at the intersection of Fulton and Burbank. I selected it because it wasn’t poverty; it was just ugly, retinal eye burn of an extreme form. On one corner was a place called Father and Me, which repaired cars. It was surrounded by rolls of barbed wire like some old lady’s hair. Across the street was a very bad trompe l’oeil lumber yard that looked like it was going to fall over. Then, there was this strange Middle Eastern restaurant in a dumpy building with a faded image on top of a man holding a chicken. It was like that in every direction.” Eventually, Klein discovered that beneath this desolate veneer of blankness were overlapping populations of Lebanese and Palestinians and Israelis, until a map of the Middle East emerged. “Little by little,” he said, laughing at the memory, “this was not the ugliest place in Los Angeles, it was just the best erased example of urban complexity. And I thought, Wow, this is one crazy city to have that much happening with so little heat you can actually see.”

To talk to Norman Klein is an exercise in excavation. It informs not just his ideas but his way of speaking, in which he keeps returning to certain subjects: the layering he sees everywhere, his idea that L.A. is less an integrated city than “like the Holy Roman Empire, nine thousand microclimates” — another favorite word. It’s a fascinating process, not least because it reflects the structure of his writing, his tendency to circle a topic, gathering impressions, fragments, evidence. “The most important aspect of his work,” says Michael Dear, professor of geography at USC, “has to do with what it tells us about how we remember: repeating stories, always embroidering. It raises questions about the very nature of remembering.” In The History of Forgetting, Klein describes the early days of the motion picture business, which developed in Echo Park. “I learned that across the street from my apartment,” he writes, “on Glendale Boulevard, Tom Mix used to ride a horse to work from his ranch in Mixville (now a Hughes market shopping center). But no recognition could be found anywhere that the entire film industry had once been centered there.” Nearly a decade after he wrote those words, Klein and I spent a few hours looking at the former site of Mixville as well as Mack Sennett’s old studio, now a public storage space. “It’s incredible,” he said. “This is the center of our whole cultural memory. This is where the language of film evolved. If we were in Paris, and this was an atelier where Picasso had painted, it would probably be a museum.” Here, however, there was nothing, not even a commemorative sign. “All cultures,” he continued, “have some kind of erasure. But what’s curious about this erasure is that it’s done mentally. In other words, you don’t see it even if it’s right in front of you.”

The rest here

photo via MAK Center / Mimi Teller

The Other Chandler: Raymond Chandler

A LITTLE taste of a documentary about the life of writer Raymond Chandler who in many ways became the "noir laureate" of Los Angeles. His detective, Philip Marlowe knew how to navigate the seamy streets and broken-down souls of Los Angeles. In this little snip you'll see and hear some of the themes we've already been talking and reading about.

"A promised city stained by crime and corruption. "

-- L.G.

Saturday, February 19, 2011

What Used To Be...

-- Stephanie Park

Friday, February 18, 2011

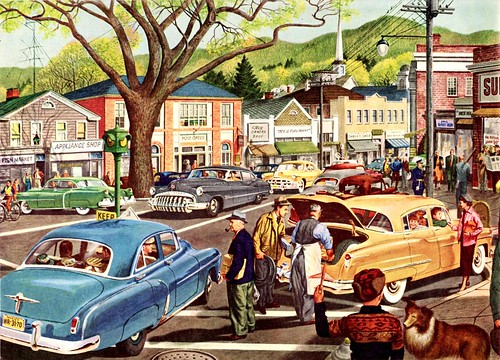

False Advertisement or Merely a Dream?

THIS PICTURE reminded me Louis Adamic's literary piece, "Laughing in the Jungle", when he wrote, "Los Angeles is probably one of the most interesting spots on the face of the earth. In it's advertisements, the Realty Board calls the town 'The City Beautiful,' 'The Wonder City,' 'The Earthly Paradise,' and other fancy names, none of which is exactly inaccurate. It is beautiful and wonderful in spots, and I guess for some people it is paradise. But that isn't coming anywhere near the truth about it..." (Ulin, 51). This advertisement as a General Motors Ad and it is set in Los Angeles. This advertisement does portray a perfect and beautiful city and it seems too good to be true..The town is lively, people are out and about, people are dressed well, and many people have cars. It really does make Los Angeles seem like a place of opportunity.

caption: Advertising LA and General Motors Car

credit: Alden Jewell, flickr creative commons

When Reality Hits

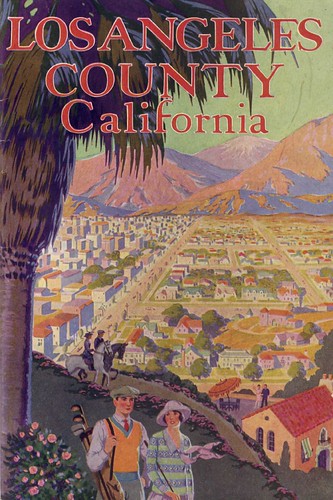

THE "New Eden": a land full of sunshine, amusement parks, exotic palaces, healing air, magical spiritualists, movie stars, property and well, land. Come out West to the new metropolis and all your problems will be solved!

This is the place that boosted in population from 11,000 to 50,000 in a single decade. At least that's what place the brochures said it was. Thousands of people moved to Los Angeles from all over the world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries based on these promises. Did they get what they expected? No, yet that didn't stop people from arriving here until it was a metropolis that far surpassed San Francisco-"the West Coast Metropolis."

The city "boosters" essentially lied to get people to come to L.A., but somehow they knew that it didn't matter if what they said was true or not, people were going to stay there. This leads me to believe that although people came here on pretenses that it would be like Utopia, they stayed here for different reasons. L.A. may have been manufactured "to look like a movie set," but it was not the "unreal city" that novelists portrayed it as for satire. It was a real place even though it was manmade and it had the qualities of life that people were looking for in a city. No, the Spanish myths weren't true and it wasn't like Athens or Spain or Italy. Los Angeles wasn't these things, but it wasn't necessarily pretending to be them either. Since everyone knew that L.A. was like a movie set, they knew that everything was "fake," or rather, imitating something else.

It should be no surprise that literature about the city was very mixed. Themes of romanticism quickly changed to satire. Novelists wrote about the outrageous in L.A., like spiritualists and cults; they also wrote about the boosters themselves. The city was virtually brand new and it must be taken into consideration that the people writing about it were new to the place. They wrote about the oddities and the main characteristics like architecture and climate but then they wrote about feelings like the "sense of dislocation and estrangement." The darker turn to literature about L.A. is due to the fact that people felt lost in such a big, new city, in my opinion. They wanted to put a label on it and they didn't know how to make it feel like home amongst the movie industry and stereotypical aspects of it. Not to mention that it was so spread out and decentralized that it was nearly impossible for it to be defined, yet writers focused mostly on "Hollywoodland" and natural disasters.

It is interesting how the writing about L.A. is as confused as the way it came together physically. The different cities within the city and so many people in one place probably created the sensation of being lost in an unreal place and dreams being shattered among all the competition. Fine illuminates the seeds of present-day L.A. because it seems as if not much has changed and writing about it today is just as difficult as it was at the beginning of the city's history.

--Claire Ensey

caption: Pamphlet by the Los Angeles Chamber of Congress in 1928

credit: Jasperdo, flikr creative commons

Banksy Writes L.A.

Loyal to Lies

---- J.Garcia

caption: "A Blue History"

photo credit: Amanda Yepiz via Flickr creative commons

Thursday, February 17, 2011

Geography of Fear

I WAS born and raised in Los Angeles. It's a city known for opportunities and dreams; a place where diversity and culture thrives. While Los Angeles may be diverse, it doesn't necessarily mean that everyone is accepting of the diversity. For me, it seems like everyone sees diversity as a norm and that the only way to go around diversity is to stay within the same circle of familiar people. In other words, segregating between cities, people, and races is the only way to get around diversity. Segregated communities and hatred between races is no stranger to native Angelenos; it's a part of our reality.

-- Stephanie Park

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

Our Oasis

THINKING of Los Angeles as a booster city is almost hard to believe; that people were led to the city on false pretenses for the purpose of creating a metropolis leaves me slightly confused. Through my understanding of Starting Points, many ideologies of LA are presented through the history of the great city. The concept of Los Angeles being attributed to as “the New Italy, the New Spain, and the New Athens” seems so cliché in that LA cannot have one cultural disposition, nor can it be defined in any such instance. In regards to that notion, it is a bizarre point to explore because in its early stages of life, the city was illustrated as the great civilizations of said European nations.

THINKING of Los Angeles as a booster city is almost hard to believe; that people were led to the city on false pretenses for the purpose of creating a metropolis leaves me slightly confused. Through my understanding of Starting Points, many ideologies of LA are presented through the history of the great city. The concept of Los Angeles being attributed to as “the New Italy, the New Spain, and the New Athens” seems so cliché in that LA cannot have one cultural disposition, nor can it be defined in any such instance. In regards to that notion, it is a bizarre point to explore because in its early stages of life, the city was illustrated as the great civilizations of said European nations. Having traveled to many places in Europe while predominantly living in the Southern California area, I have found that this reference to LA having any Mediterranean appeal is completely false and most likely did not emulate any of the aforementioned identities in any of its previous history. Los Angeles has its own culture; more than likely because it was established on an artificial reality. The allure to Los Angeles referred to within the article depicted the city as “the New Eden” which provokes the images of an oasis; a place where everything is perfect yet the irony of temptation and corruption insinuates more of the stereotypes of Los Angeles present today.

In one of the last passages within the text of Starting Points, it is said that since the booster era, over a century has passed and LA is still a destination of settlement and migration. This appeal of Los Angeles began over one hundred years ago, and is still highly present today. At what point in time will people no longer want to venture to the highly polluted city-at what point will people come to the region, see the overwhelming lifestyle, and want to turn back in hopes of finding a new place to call home? It seems as though Los Angeles will, literally, be the “New Rome”. The city will build on top of itself for years to come, and people will flock to the renowned city to live in the oasis and drink from the fountain of youth. Because LA is purely that- LA is a legend. Whether or not the legend is true, well, that’s for us to figure out on our own.

-Chelsea Vogt

photo via publicartinla.com

Tuesday, February 15, 2011

L.A. Noir is now "L.A. Noire"

NOW this makes me what to be a gamer. The attention to detail is pretty amazing. And check out the L.A. Times building near the top of the trailer.

-- L.G.

Monday, February 14, 2011

La Migra

GROWING UP, Los Angeles was the older brother I never had. LA seemed cooler, rawer, more exciting, slightly dangerous, and above all, different. Visions of grandeur suffocated my mind as I imagined living the A-life: cruising Sunset with the next big thing wrapped around my arm, jaunting to the hills for 360° parties, lazy beachside living on some private Malibu stretch. This seemed just a taste of the good life I hungered for. The longer this notion ate at my stomach, the more the pangs turned to nausea.

My quiet perch in San Diego left me yearning for a new outlet. I constantly ridiculed my father’s exodus from LA thirty years prior, unable to fathom any motives for leaving a seeming paradise. I felt I was riding the bench while these Angelenos were stealing all the showtime. But my perspective was lost in the haze to the heart of LA.

As a child, LA only really began when I drove past the Holiday Inn (now Hotel Angeleno). Visits to Grandpas’ house firmly rooted the LA of yesteryear in my mind; living in a virtually unchanged Paul William’s home from the early 30’s kept the lonestar this-world-is-my-own feeling so fervently espoused by current Westerners (the same Range Roving patrons now set in their ivory towers). I want this return to simplicity.

My feelings are mixed. I hated this town my first full year in residence. I felt trapped, insignificant, someone else’s doormat. The overwhelming allure of the town hooked another baitfish, but I soon found my outlets of escape.

The 405 is clearly in cahoots with Satan. Though this devilish path hampers my daily travels and often is the number one scheduling factor, it is also the introduction to my sanctuary. More mixed feelings. Until I arrive at Highway 395, then the bliss takes the wheel and doesn’t stop for all the weeks spent on top of the world in my Mammoth heaven.

Los Angeles cannot be defined, much in the same way I cannot define my experience living here. It's a launching pad to the rest of the world, where a day's travel inside or out of the city leaves nothing to the imagination. I do know there is an exorbitant amount of bullshit to wade through, but I also know the reward of finding the perfect niche in this Renaissance land.

--Weston Finfer

caption: the erstwhile holiday inn @ the 405

credit: chase stone

Prospective Perspective Amid an Angeleno Collective

There are so many aspects that make LA unlike any other city around the world, something I have come to understand as a result of ‘getting cultured’ from a global perspective. A six-month work/study experience in London, UK helped me develop a series of coping skills which increasingly allow me to enjoy my time here – simultaneously allowing room for creative analysis. For example: LA can be a confining city if you have no means of transportation, so I found a way to get around. The air quality is horrible at times, another issue of mine, so getting away into the mountains for a hike really makes all the difference, and hits the reset button.

Although overall my perception is still changing, growing, evolving, I can say that living in this city has expanded my perception of place, space and the influence one's attitude toward them can have on the overall wellbeing and success of an individual

-- Ryan Cavalier

caption: A Lens Lit View of Reality

credit: Ryan Cavalier

How Far Will It Go?

THE more I learn about the history of L.A., the more I am inclined to not want to be from here. The rapid growth in population was due to an idea that never existed. People chased after a land and a lifestyle that they thought could take away their problems and worries. Competing with San Francisco for size and popularity, the two rail lines that made it happen were the Southern Pacific in 1876 and the Santa Fe in 1886.

THE more I learn about the history of L.A., the more I am inclined to not want to be from here. The rapid growth in population was due to an idea that never existed. People chased after a land and a lifestyle that they thought could take away their problems and worries. Competing with San Francisco for size and popularity, the two rail lines that made it happen were the Southern Pacific in 1876 and the Santa Fe in 1886.In the ten years between 1880 and 1890 the population grew from 11,000 to 50,000. Outgrowing San Francisco was no longer a concern due to the room that southern California had for expansion.After the 1930s, Los Angeles had a population of 2.2 million and was the second largest city in the United States, competing with New York for being the most culturally diverse. I am proud of Los Angeles for its multi-ethnic background, but I am ashamed at the behavior of the “Anglos” towards the other races in the process of settling. The old southern California idea of Manifest Destiny disappoints me and I wish I could have been around to tell Horace Bell and the Los Angeles Rangers exactly what I think of them and their vigilante behavior.

It’s understandable that the people of Los Angeles would use the sunshine as propaganda to promote the region, but labeling it names such as the New Italy, New Spain, and New Athens is taking it a little too far. Not to mention the terms New Eden and Holy Land-- as if the people here lived in complete peace and harmony with one another. I agree with Carey McWilliams when he said that the overwhelming migration to L.A. may have been the largest but it was “the least heroic.”

The continuation of expansion due to the aviation industry, the Pacific Electric rail lines, and the Auto Club spread the outer boundaries of L.A. north to San Fernando, south to the harbor, and west to the coast. With new land came new divisions that are still seen today. It’s interesting to see the breakdown of territory in the mid 1900s and how much things still haven't changed. The Westside of Wilshire and Sunset was home to the Anglo’s, while the East L.A., Boyle Heights area was dominantly Mexican-American. South Central, commonly known as Watt’s, was inhabited by the African American community and I suppose it has changed a bit today because now it includes a community of Asians and Latinos.

Angeleno’s dared to label Los Angeles as the "American Dream Capital, keeper of our national fantasies.” Is that a joke? Sunshine and a couple movie sets don’t make up for the lack of cultural unity and intense racism that was rampant in all areas of L.A. What makes it even worse is that there are still traces of that same racism and segregation today. People are so busy “chasing the dream,” that they couldn’t and still don’t see Pandora’s jar lying open and empty. Is it safe to say that hope has finally escaped? Have we dug ourselves in a hole so deep that it’s going to take more than 4,083 miles of track to reach down and pull us out?

-- J. Garcia

Boostering the Angeleno Playground

caption: example of mission revival architecture

credit: via sixmarinis and the seventh art

A Fantasy Without a Past

IN David Fine’s chapter, "Starting Points" L.A. was boosted into existence with no presentation of its past but all the hope of the future. This “new world” almost immediately caught the eyes of people from all over the nation because they could make the land what they wanted, a sort of personal Utopia. Whether it was because there are not many permanents such as restrictions on land or beliefs, or the culturally diverse background of the people of L.A. that welcomes newcomers, but people keep on traveling to see what all the fuss is about. The other helpful boost comes from advertisements and their use of grandiose words. With words like sun-kissed, Utopia, fantasy, happiness, who wouldn’t want to come here?

IN David Fine’s chapter, "Starting Points" L.A. was boosted into existence with no presentation of its past but all the hope of the future. This “new world” almost immediately caught the eyes of people from all over the nation because they could make the land what they wanted, a sort of personal Utopia. Whether it was because there are not many permanents such as restrictions on land or beliefs, or the culturally diverse background of the people of L.A. that welcomes newcomers, but people keep on traveling to see what all the fuss is about. The other helpful boost comes from advertisements and their use of grandiose words. With words like sun-kissed, Utopia, fantasy, happiness, who wouldn’t want to come here? Writers also were interested in coming for the oddballs and stories that come with L.A.’s unusual landscape. With the advertised curative nature of the climate, racial conflicts, and unreality, it is not hard to imagine a story that intertwines all of these themes. Like Joan Didion says “no one remembers the past”, but these visitors and outsiders are ready to interpret and tell the future of L.A. on the pages of a book. These storytelling themes have not only reflected how the city began to come together but actually shaped L.A. physically.

Though there are designated city limits, the true shape follows no boundaries. Throughout this city, microcosms have been created for every culture and motivation. There are places like Koreatown and Downtown for the multicultural ethnics and then there are places for the film industry and corporate. One interesting difference noticed in Fine’s Chapter is the local versus movie set architecture. This reflects not only the actual use of buildings needed but the give in that the city allows to keep on attaining this romantic notion of a fantasy place where buildings can be created for any desire.

There are quite a few factors of this chapter that are personally illuminating. The first, being the lack of privacy that was brought up in the first page. Like any other city, we have buildings right up next to each other, but I think privacy would also be in the sense that our stories are constantly being told and examined. There is no place to hide for those oddballs out there. Like one author puts it, we are a “splendid sideshow” to be written about for many eyes to read and learn about. Especially learn from the natural and man-made disasters that seem to come about every decade or so, that seem to really bring the news light illumination.

There are still many of the same stereotypes and false promises of Utopia in present-day L.A. A city that seems to keep on growing, and city limits don’t define, the land of fantasy catches foreigners’ eyes everywhere. I went abroad last year, and when I told my new friends where I’m from, it almost seems like the only city they know in California is the allusively seductive L.A.

--Jessica Fernandez

caption: Santa Monica state beach

credit: denizoran, flikr creative commons

Boosting on the Page

IN the reading, David Fine argues that Los Angeles was “boosted” into existence for a variety of reasons, taking into account historical, literary and cultural situations. As a history Major, I found it interesting when he discussed the development of San Francisco as a city, with Los Angeles being the “new instant city being manufactured” in 1897. From this moment on, diversity proved to be a crucial element of the city, making it an immigrant destination where various nations and languages came together. I feel that this has an enormous basis for the Los Angeles we have today (specifically seen with destinations like Little Ethiopia and Little Tokyo). Next, Fine explored how Los Angeles came into existence through “the page”. Immediately this quote from Fine caught my attention: “Los Angeles fiction is about the act of entry, about the discovery and the taking possession of a place that differed significantly from the place left behind…by a sense of dislocation and estrangement, is the central and essential feature of the fiction of Los Angeles” (p.15). Those who began to write about LA were viewing it from the outside as new migrants to the city that was still in the crucial stages of development. However, even today I feel that this applies to me. I tend to look at LA from the outside myself, which means my writing may show that I am experiencing Los Angeles just as these writers were. These writers went about encompassing how they felt about the city (or even how they wanted to feel about it), and represented it on the page for others to see, adding to the mythology of Los Angeles, whether or not it was fact or fiction. Fine ended this article with an interesting quote; “Twentieth-Century fiction about Los Angeles is less a collection of hate mail to a beleaguered city than an expression of anxiety about the modern condition”. Through this reading, he was expressing how the booster mentality that was so evident in the beginning years of Los Angeles has been lost. But those now writing about this city are not viewing it begrudgingly, but almost longingly, to return to how the city was once viewed instead of what may come in the future

--Reilly Wilson

photo: union station passenger terminal

credit: via hidden l.a website

Sunday, February 13, 2011

Got Boosties?

CURIOUS how the mode of transport that laid the tracks for LA’s arrival became almost instanly eradicated from the city’s conscious. The Southern Pacific and Santa Fe railways of the late 19th century brought the masses to the Holy Land, and all for the low price of $1. I like that, the idea of walking to the rail station with 4 quarters, maybe seeing a McDonald’s, pondering on whether to order a dollar burger or small fries and ultimately deciding on a trip to California. Obviously inflation plays a role in this dream, but c’mon, a buck is a buck. Adhering to the mirage quality that birthed and raised Los Angeles to its fantasy factory status, the railways planted a seed and quickly withered from the expanding streets run ragged by automobiles.

It’s a golden land, the Golden State, holy according to some latitudes, green by longitude. Opportunity exploded in the fertile basin, the ready-made canvas landscape beckoning a pilgrimage to paradise from notables in all vocations. An expatriate town if there ever was, LA has and continues to attract misfits, hopefuls, has-beens, will-becomes, never-had-a-chance’s, and the terminally-chillers. Writing about a town constantly evolving brought a creationist aspect to the author’s role in promoting the myth and aura of an oasis lifestyle. Drawing on memories of homesteads prior along with visions of grandeur allowed the collective imagination to know no limits, flowing into the architecture, art, and aesthetic of the land.

Maybe this is the apocalyptic land of lore. We run into the ocean, pants down, as hillsides quake into pieces and canyonscapes blaze in glory, all the while denying our existence in the face of losing another day to Death and begrudging another wrinkle to Gravity. Gladly, I submit to the femme fatale nature as the ongoing boosters hark a miracle that may or may not exist.

--Weston Finfer

photo: beverly hills hotel

credit: chase stone

Saturday, February 12, 2011

haze

LOS ANGELES’ head is a bit fuzzy. It affects us all. From the lungs spew the smoke. And the addiction has passed to me, secondhand. I drink the sulfur and breathe the filter. Because it revitalizes me. I question why I do it. Every drag in makes the out that much harder. But it’s the questioning that moves me.

As I watch the sky shade from blue, to orange—the atomic descent—to pink, to purple, and the wonderful in-betweens that linger longer than the primary impression, night falls upon California’s chameleon city. First noticeable is the expanse of midrange building—cookie cutters from Hells Kitchen—that trick the eye into the monotonous maze of Sin’s suburb. This sprawl goes on for as long as the eye can see—correction, for as long as the eye is allowed to see. The margins become lost in the mist. This mist—or fog, smoke, haze—is untouchable, yet a part of us. It has permeated the city’s conscious, instilling the reality of a surface life. Looks to the horizon find a limited perspective, a 10 mile radius at best to asses the depth of this land. We fear what we can’t see. We fear the world outside our bubble. So we restrict depth perception. We view people for whether they model clothes or simply wear them; whether they get from point A to B or arrive in style; if their cash rolls or bounces; if their skin screams appeal, or just the first peel. The surface is a beautiful thing, for awhile. Then we become acclimated. From there, one can settle, or one digs deeper. I see you, shrouded, outlined, and willing to be defined. Your Otherness I shall conquer.

photo credit, weston finfer

Friday, February 11, 2011

The Outsider

LOS ANGELES was boosted into existence by a mixture of several things. Los Angeles initially emerged as a result of the land boom that was made possible by the rail lines leading into Southern California. It grew over the next several decades as a white Protestant community paving over the Mexican Catholic heritage that came before it. As a network of highways and roads were built and the separate neighborhoods became connected by the automobile, the city began to grow into what we know today as Los Angeles.

After reading about the history about Los Angeles, it seems to me that most of perceptions and writings about LA sprung out of the physical geography of the land. As a diverse, widely spread out city, many people became frustrated with how to describe or summarize such an assorted group of neighborhoods. With the beach, mountains, and desert all rolled into one it was difficult to characterize the city as a whole.

Another characteristic of LA that seemed to both bother and puzzle people was the lack of a single type of architecture. With the influence of Hollywood, much of the architecture seemed to be model a movie set. Rather than having a uniform style of architecture like New York or San Francisco, the landscape for Los Angeles was built more on a “propensity for fantasy creation,” as David Fine puts it in his book Imagining Los Angeles. Even today, one of the most iconic places in LA is Randy’s Donuts, where a giant 23-foot doughnut sits atop a tiny drive-in. This is the architecture of Los Angeles.

What I found personally illuminating about Fine’s piece was when he was discussing the reason for why LA literature was virtually nonexistent until around the 1920s. It wasn’t because there was nothing to say about the city or there were no gifted writers, it was simply because virtually everyone was new to Los Angeles. The writers in LA were themselves outsiders, newcomers to the land, and therefore unconnected to the city. Fine uses the great example of Mark Twain. Though Twain began his career in San Francisco, all of his writing were reflective of his home back in the Midwest. Fine describes the literature of the city perfectly stating, “The distanced perspective of the outsider, marked by a sense of dislocation and estrangement, is the central and essential feature of the fiction of Los Angeles.”

You can still see that evidence of the outsider everywhere around LA. Being on a campus where almost half the students come from out of state you can see how most of LA’s population consists of people caught between, “a Southern California present and a past carried from some other place.” Because L.A. lacks a sense of uniformity or its own sense of style, it becomes a struggle to grasp the concept of city or describe it in a single way, which is why so many people are frustrated with Los Angles.

However, I believe that this absence of style is in itself, the “LA style.” As Fine, so perfectly describes it, “In the absence of a dominant style, every style and manner [has] found a place.” LA is indeed a place where anything goes; where nobody fits in but everybody fits in. LA is the outsider portrayed in so many of the movies produced on its land. It’s the newcomer, the underdog. And although it’s had its fair share of struggle, LA has become the hero for so many other outsiders looking for a place to belong.

caption: "griffith" (the old zoo at griffith park)

credit: OmarOmar, flickr creative commons

The New Italy, the New Spain, the New Athens

SAN FRANCISCO was known as the city but it was Los Angeles that grew immensely and steadily throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s. With the instatement of two rail lines into Southern California, Los Angeles began to emerge and flourish. At first, the “cow counties” were populated by a group of migrants made up of mostly white, middle class Protestants that bought into the spectacular marketing scheme that Los Angeles had to offer. By the 1920s, Los Angeles tied San Francisco’s population, but it was Los Angeles that had a secret weapon: space. Los Angeles spread across land from the San Gabriel Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, making it possible for the population to increase at rapid rates.

SAN FRANCISCO was known as the city but it was Los Angeles that grew immensely and steadily throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s. With the instatement of two rail lines into Southern California, Los Angeles began to emerge and flourish. At first, the “cow counties” were populated by a group of migrants made up of mostly white, middle class Protestants that bought into the spectacular marketing scheme that Los Angeles had to offer. By the 1920s, Los Angeles tied San Francisco’s population, but it was Los Angeles that had a secret weapon: space. Los Angeles spread across land from the San Gabriel Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, making it possible for the population to increase at rapid rates.What boosted L.A.’s existence were the imperative connections it had. Journalists were added onto the railroad payrolls so they would have an incentive to boast about the “year-round sunshine” that came with living in California. It was these publicists that worked with city boosters, much like Los Angeles Times owner Harrison Gray Otis to promote the region. Even after Otis died, the Times collaborated with the Chamber of Commerce and the All Year Club to endorse L.A. as “the West Coast metropolis.” L.A. was an escape from the overcrowded East. People still tend to see Los Angeles as that. They leave their snow-filled hometown and retreat to the southern California beaches. When I go back home, I constantly get asked why I’m so pale, as if they think I spend every day under the bright California sun. I myself was disappointed after spending last summer in L.A. only to find that it didn’t live up to its reputation, that the June Gloom never seemed to end and the days at the beach were few and far between.

Being the spread out city that it was, Los Angeles was equipped for the arrival of the automobile. With this came the Auto Club and tourists, Disneyland and Magic Mountain. I would love to learn more about the influence the automobile had on the creation of the city. What I understood from what David Fine said in his book Imagining Los Angeles, was that the automobile did not have any influence per say, but rather the city was prepared for the use of them. It wasn’t until recently, as I was driving along the 405 with one of my California-native friends that I was informed about the car industry’s involvement in the making of the layout of the city as it is today.

If you look at present-day Los Angeles, you can see the clear separations of the different communities. Before the railroad came about, the city was made up of Mexicans, Indians, Anglos, and Chinese. There were plenty of racial conflicts, so the white Anglos took control of the land. They began to see the darker-skinned population as “dangerous aliens and foreigners” who, from the eyes of the Anglos, were a threat to the community and any progress that needed to be made. Because of their ignorance and racism, there are modern ethnic neighborhoods that have been extended from the past.

The history of Los Angeles can be seen in the fiction that was written during the time the city was being established. Although there is so much literature from this time, one must keep in mind that the writers were “outsiders, newcomers, visitors” to Los Angeles. Therefore, the majority of the written work was about the differences between the East and the new West. Displacement and estrangement played major roles in the fiction, the authors focusing on themes of “unreality, masquerade, and deception.” Although fiction, it is these themes that influenced the people of the time, bringing a whole new light to California. Unfortunately, the fiction of this time, and even the newer fiction that comes in the form of screenplays and movies, has become more factual than not. Hollywood has overtaken all of Los Angeles, becoming the image for how people are supposed to represent themselves. We have all taken on roles, characters of a movie that should be called Reality. Yet, despite all this, Los Angeles still holds some sort of appeal to those on the outside looking in.

-- Jackie DiBiase

photo: Close-up of Hollywood sign, Hollywood, California, USA

credit: Michael Dean Roberts

Thursday, February 10, 2011

Inventing LA: A Film Review

THE film "Inventing LA" provides an in-depth analysis of how one man began the Los Angeles Times, a newspaper which he used to push his own political and economic agendas, which ultimately played a major role in determining how Los Angeles came to be spatially, economically, and socially. The analyzes the grit and determination of Harrison Gray Otis, his successor Harry Chandler, and their ruthless attack on whatever posed a threat to their voice, their power, their catalyst, the Los Angeles Times. I highly recommend this documentary to anyone interested in the development of Los Angeles, Southern California real estate and an iconic Los Angeles.

THE film "Inventing LA" provides an in-depth analysis of how one man began the Los Angeles Times, a newspaper which he used to push his own political and economic agendas, which ultimately played a major role in determining how Los Angeles came to be spatially, economically, and socially. The analyzes the grit and determination of Harrison Gray Otis, his successor Harry Chandler, and their ruthless attack on whatever posed a threat to their voice, their power, their catalyst, the Los Angeles Times. I highly recommend this documentary to anyone interested in the development of Los Angeles, Southern California real estate and an iconic Los Angeles.Monday, February 7, 2011

What's In A Boost?

L.A.’s initial growth comes from people who oppressed a marginalized group for financial gain and power. While this finding is unsettling, it is hardly original and at least as Angelenos we can pride ourselves in the fact that we did not begin this trend. In his book, Imagining Los Angeles, David Fine, in delves into this idea more in-depth, “The old Californios, the ‘first families’ who held the land grants, were unable to defend their claims in Anglo courts – unable to pay the legal fees much less to understand the laws that were disenfranchising them – and so lost their lands, piece by piece, to Yankee speculators,”(Fine 6-7). And after these “first families” are eliminated, the possibilities for this space called Los Angeles become literally limitless. For the love of God, we brought irrigation to the desert. Railroads initially created a way for Americans to get to the city, “the Southern Pacific in 1876 and the Santa Fe in 1886,” coupled with, “…land speculators, subdividers, city boosters, and railroad tycoons,”(Fine 4) created a mixture from which Los Angeles did not have a chance to be unsuccessful.

What I personally found to be so interesting is the fact that while the railroad brought people to the city, it is the invention of the automobile that designed the city’s layout. Fine writes, “In contributing to the decentralization of the city, the automobile diminished the central city’s hegemony,”(Fine 9). The same invention that plagues our freeways now is also responsible for the disjointed nature of Los Angeles and its surrounding suburbs. The fact that the city is so disjointed from its genesis speaks to the fact that Los Angeles can still be considered as divided. People from the South Bay dread having to go five miles East, because God forbid they find themselves in Hawthorne. Celebrities that live in the Hollywood Hills never venture to downtown; exceptions include filming and soup kitchen publicity stunts.

Another interesting development for the city is also probably the most well-known: the development of the film industry. The obvious reasons for this include: “the region had plenty of sunshine, open space for outdoors shooting, and a varied landscape,”(Fine 12). The final reason is particularly sinister, and contributes to the over-all “scummy nature” of Angelenos. Los Angeles, “also had the appeal of being 3000 miles away from the Edison patents,”(Fine 12). First we remove landowners from the city by means of forcefully taking their land, and then our major industry exploits the ingenuity of one man’s developments.

But remember, to me, Los Angeles is like a younger sibling; I can trash on it as much as I want but the minute a “non-local” wants to say horrible things about it, I feel the need to defend this city. I feel compelled to defend the boosters, the tycoons, the celebrities. But I also feel like we can’t turn a blind eye to all the horrible crap that is a part of our city’s development. So what’s the “fair” thing to do? I guess it means just loving Los Angeles for what it is and for what it has become, while acknowledging the glaring faults as well.

--Hailey Hanann

caption: I-8 Meets California 125

credit: Allan Ferguson, flickr creative commons

You Can't Hide Behind the Palm Tree

IF you're from Los Angeles, the image of the palm tree is both completely alluring and cliché. However, the palm tree in fact isn’t a tree at all; it’s actually more closely related to the grass species. This large lawn tossing, this giant grass tree, embodies the city in more ways than we’d ever stopped to consider. Standing erect, shallow roots intact, the palm tree towers over residential areas snubbing its nose (in this case fronds) at those beneath it. Painfully slender, this enormous shoot of grass stands erect and above the frumpy oak and average maple. Its larger than life quality has fully become the personality of LA. But, I think its done so in all the wrong ways.

IF you're from Los Angeles, the image of the palm tree is both completely alluring and cliché. However, the palm tree in fact isn’t a tree at all; it’s actually more closely related to the grass species. This large lawn tossing, this giant grass tree, embodies the city in more ways than we’d ever stopped to consider. Standing erect, shallow roots intact, the palm tree towers over residential areas snubbing its nose (in this case fronds) at those beneath it. Painfully slender, this enormous shoot of grass stands erect and above the frumpy oak and average maple. Its larger than life quality has fully become the personality of LA. But, I think its done so in all the wrong ways. Assuming that the palm “tree” represents the shallow nature of Los Angeles, we’d have to agree that Los Angeles is superficial in the first place. I’d have to agree: people cut each other off in traffic, give each other the finger, neighbors shoot each other over colors or street corners, and “industry” divas will rip out even the most expensive extensions for the allure of fame. We live in a city where “please” and “thank you” are rarities, and the only apologies ever uttered are “Sorry, I’m not sorry.” We don’t interact with our neighbors, we shut our doors and lock the deadbolt because we fear our neighbors. Just yesterday a student at Gardena High School critically injured two of his classmates when a gun in his backpack accidentally went off in class. Reporters scornfully ask whether the high school freshman will be tried as an adult, why the school didn’t have metal detectors, and what the chances are of survival for the two injured. However, did anyone stop to ask why the student felt the need to bring the gun to school in the first place?

Interestingly enough, we cannot find salvation under a palm tree; the leaves are dwarfed in comparison to the trunk. You can even say the tree is slender enough that you can’t hide behind it either. Maybe this image gives us more than what we originally would have thought. We can’t hide from our superficial notions, our traffic, or our lack of humanity for one another. And maybe so many people come to Los Angeles because they want a place to hide.

--Hailey Hanann

photo: "Little Palms, Mid-Town"

credit: L.G.

Thursday, February 3, 2011

Mike the Poet: "Alive at LMU"

HERE is a little poetic reprise from our guest last night, Mike Sonksen, better known as, Mike the Poet. Sonksen has worked variously as a journalist, teacher and L.A. tour guide. Los Angeles is not only his hometown, but his mighty subject and his muse.

Stay tuned to this space, and I will reblog Sonksen's "Favorite L.A. Books" reading list.

Wednesday, February 2, 2011

Iconic Los Angeles and The Perpetual Issue of Warmth

There is a great deal of California in what I consider to be Angelino, and vice versa. If California and Los Angeles were individual tapestries, they would sample from the same material – but ultimately hold their individual integrities and aesthetics. It is in this way that I have come to analyze Los Angeles – in light of its role in defining California, yet not ignorant to California’s suckling from the sun-tanned teat of all things Angelino.

We live in a city of colors, a city of scents, of dollars, of determination – a city where sunsets succeed hour-deficient days, a city whose citizens are cultured on consumerism and dance in the sun-casted shadows of swaying frivolities. Los Angeles has so many hues, scents and textures that choosing one would demean, and overall minimize the vast depth and breadth the city, and region have to offer. I will delve into one such medium I feel is iconically ‘Los Angeles’, and ascertain why they are so.

Upon reaching the final two weeks of my six-month stay in London, England this past year I very much longed for California. In an effort to block out the freezing weather, the brevity of sunlight on whited winter days, and ultimately to prepare myself for the Angelino life I so clearly envisioned. More tangible than anything else in this vision was the notion of warmth. This sense of warmth I so specifically remember, and quite literally felt on my skin, was a placeholder for all the times I myself had melted under the overpowering warmth of the sun – and done nothing but feel its presence upon my skin, and repeat.

I want to specify the type of warmth I’m talking about – because there are varying types transcending different and specific sensations. Being from the north of California, albeit a place of temperate weather and kind temperament, warmth is often categorized by the lack of fog, or is defined by what is expected but either does not arrive or is fended off. Warmth is refreshing, warmth is relaxing and it is a privilege.

Angelinos expect their warmth; they want to be able to control it with their own fingers, to succumb to its increasing comfort like an adjustable shower handle. I too came to desire a dial which could control the warmth, to reject the world’s realistic weather patterns, burn away valleys of fog, melt frozen street grout, and idealize the elements. This warmth is so iconically Los Angeles because Angelinos live in an unrealistic climate, especially when compared to the rest of the world.

This commitment-cancelling warmth which I tie so intimately to Los Angeles is so because I clearly see the following: as was discussed in previous articles, the Los Angeles area is one in which the people battle against the landscape and elements (in an uphill manner) to preserve their highly coveted way of life. Just as Angelinos defy logic by settling (in the masses) in an area with an inadequate water supply, with desert conditions, perched next to the ocean – which to has rapidly become overcrowded, sprawled and polluted so as to further my claim –they now perpetuate this notion of ridiculousness by continuing to live here, in an area deficient in life’s bare necessities, but abundant in pleasurable pursuits – such as exercising one’s will in order to attain that sense of warmth. I too am ridiculous, sun-seeking, and excited to stay in this topographical who-done-it for as long as necessary. The question remains: what will we, and the next generation need to do in order to preserve this stellar mental placidity?

-- Ryan Cavalier

Tuesday, February 1, 2011

It's the Water:

L.A. had to be wrestled into existence. One of the tropes you will hear, time and again, is the saga of the water wars. L.A. was --and is -- a desert. Without water, the city wouldn't have bloomed. Boosters -- businessmen, land speculators, the railroads -- had already embroidered more than a little on the L.A. narrative -- remember the citrus crate boxes we talked about last week? -- but big business saw a Utopia in the parched desert so close to the sea.

History tells us that what became to be known as "the water wars" began when Frederick Eaton was elected mayor of Los Angeles in 1898. He appointed his friend, William Mulholland (yes, that Mullholland), to head up a new city agency, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP).

Eaton and Mulholland's vision stretched far greater than the little Pueblo that was founded in 1781. They set their sites on the run off from the Sierra Nevada river that ran through Owens Valley. The plan was to build an aqueduct that would deliever water to the basin -- essentially literally de-hydrating the Owens Valley -- its people and its prospects -- to allow L.A. to flourish.

It took nearly eight years,2,000 workers and the digging of 164 tunnels to complete the aqueduct in 1913. Water from the Owens River reached a reservoir in the San Fernando Valley on November 5. During the opening-day ceremony, Mulholland spoke these famous words: "There it is. Take it."

After all, he did.

photo caption: Dynamite found during a string of sabotage incidents along the Owens Valley Aqueduct

photo credit: image via Wikipedia Commons, circa 1924